Episode 19: Grandfathers of History, part 3

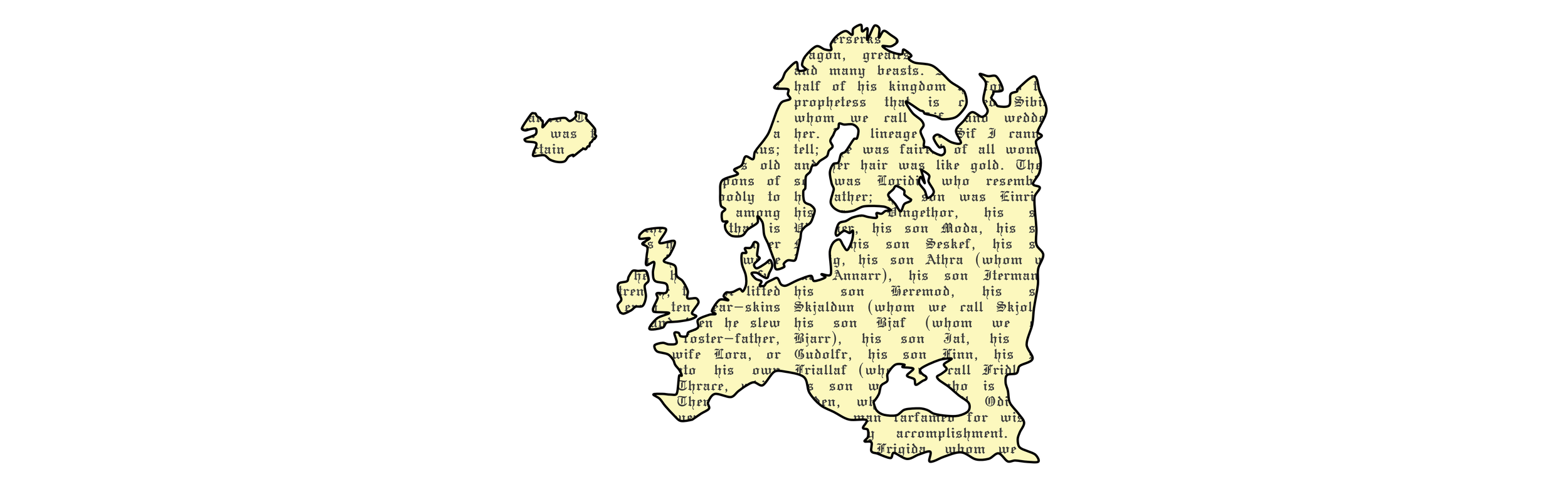

Some evidence suggests the branches of the European family tree… go back to the same trunk.

All the quotes from the Bible for the main story were were taken from the English Standard Version or the New King James Version. For the other sources, including commentaries, websites, or articles, you can find links and references in the show notes below in the order they appeared. If you have any questions, there’s a link to contact me at the bottom of the page.

Show notes:

For an overview of the spread of Greek civilization and the invasions of Alexander the Great, see here.

For the area covered by the Roman empire, see here.

For a the fall of the Roman empire in the west, see here. Before this fall, the Roman empire split into eastern and western parts (see here). The eastern, Byzantine, empire spoke Greek and lasted until it was conquered by the Ottomans in 1453 AD (see World Encyclopedia entry here).

For the background of Josephus, see here.

For Josephus’ comment about Greek renaming nations around them, see sentence beginning, “The Greeks who became the authors of such mutations,” here. It is unclear if Josephus’ identifications are all correct as scholars don’t always agree with him (see later show notes) but it does give a lead to use in trying to figure out where Japheth’s kids went.

For a list of Josephus’ sources, see here.

For references that connect Togarmah to Hittite and Assyrian inscriptions, see Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association. For the Hittites living in Asia minor, see reference here. For the Taurus mountains reaching to Lake Van, near Armenia, see here. I left out the reference to Armenia in this case as the comment regarding the Halys river in the above commentary is also in central Turkey, so the emphasis appeared to be on that region rather than the direction of Armenia, though it did mention that the Armenians apparently trace their ancestry back to Togarmah. There is also a reference in Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170-171). Pacific Press Publishing Association to Assyrian trading colonies that appear to be related to Togarmah located in central or south eastern Turkey.

Josephus says that the descendants of Togarmah were called the Phrygians (see sentence containing, “Thrugramma the Thrugrammeans,” here. The note on pg. 541 here says that Phrygia had fluid borders but extended to the center of Asia minor.

For a list of Jewish scholars cited as connecting the Turks to Togarmah, see the note on Genesis 10:3 here.

The tradition Togarmah settled in Armenia is given by Moses of Chorene from the 400s AD (which like most ancient documents, may or may not be accurate, see pgs 897-898 here) and says that Haik, the ancestor of the Armenians was the son of Thorgom the son of Gomer (see note on Genesis 10:3 here. Several sources come to this conclusion, though it is not clear how many rely on Moses of Chorene. See notes on Genesis 10:3, here and here. See also note on Genesis 10:3 here which mentions a number of alternatives including Cappadocia in Asia Minor and Crimea among others before concluding that Armenia is the general conclusion based on Moses of Chorene. Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers suggests that Togarmah was probably either Scythian (see other show notes) or Armenian. Armenia today is smaller than it was in the ancient past as noted by the entry on pg. 564 here.

Scholars suggest, based on Greek tradition and the similarity in language, that the Phrygians originally came from the region around Greece, not from central Asia. Taking all this into account, and noting the local legends in Armenia suggest descent from Togarmah, I’m inclined to say that Togarmah’s descendants lived from central Turkey, Asia Minor to modern Armenia. As for the Phrygian element, I wonder if the descendants of Togarmah and emigrants from Greece called the Phrygians occupied the same areas in central Asia Minor and mixed with one another, leading to Josephus identifying Togarmah’s descendants as the Phrygians, but this is my speculation. See note on Genesis 10:3, here where the options span the region from Turkey to Armenia.

The name “Riphath” is no longer known in the world according to the note on Genesis 10:3, here. For Josephus’ reference to Riphath’s children being called the Paphlagonians, see sentence starting, “So did Riphath found,” here. See also note on Genesis 10:3, here. Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association notes that Paphlagonia’s capitol was Sinope, located on the Black sea coast according to the article here.

For the suggestion that the Rhipaean mountains were named after Riphath, see notes on Genesis 10:3 here and here. For an entry on the Rhipaean mountains, see here.

In place of “Riphath,” 1 Chronicles 1:6 says “Diphath.” The commentary note on Genesis 10:3, here points out that the letters “R” and “D” are very similar in Hebrew. A similar difference can be seen in “Dodanim” and “Rodanim” that came up in the last episode. See also note on Genesis 10:3 here.

For the Riphaean mountains being at the edge of Greek geography, and considered somewhat mythical, see here.

For one commentary suggested that the Riphaean mountains were what we call the Carpathians in and around modern-day Romania (see note on Genesis 10:3, here. For the Carpathians being in modern-day Romania, see map here and definition here). The more common belief that the Riphaean mountains are the Ural mountains, see chapter 24 of Pliny, here (and notes) and book 7.3 of Strabo’s geography here with footnote 32. See also note on Genesis 10:3, here that considers all the identifications, from the Paphlagonians to the Caspian sea, to be “uncertain.”

For Ashkenaz settling in Armenia, see the commentary note on Genesis 10:3 here that points out that Ashkenaz is named in Jeremiah 51:27 in connection with Ararat which people link to the area in and around Armenia. See also notes on Genesis 10:3, here, here, and here. as well as Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers.

For the ancient Assyrian reference to the “Ashkuza” who lived south of modern-day Armenia and might be connected to the descendants of Ashkenaz, see Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association and Horn, S. H. (1979). In The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary (pp. 87–88). Review and Herald Publishing Association as well as Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association.

For reference to locations named one form or another of “Ascania,” see the note on Genesis 10:3 here. See book 12 section 3 here for a reference to an “Ascanian Lake,” and book 14 section 5 for reference to an Ascanian lake, river, and village in Mysia here. For the location of Mysia, see entry on pg. 464 here. See also note on Genesis 10:3 here that mentions locations named Ascanius or Ascania in Bithynia in northwestern Asia minor (see entry on pg. 12 here).

According to footnote 1 at the bottom of pg. 25 here, the Black Sea was originally called “Axenus” which meant “unfriendly.” For speculation that “Axenus” is related to Ashkenaz, see notes on Genesis 10:3 here, here and here as well as Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers. See also note on Genesis 10:3, here, though this is a summary of what others think.

The commentary note on Genesis 10:3, here mentions a reference by Pliny (unclear if it is the elder or the younger) who spoke of the “Ascanitici” living on the shores of the Paulus Maeotis, what we call the Sea of Azov today (see here) but I couldn’t find other references to this people when briefly searching Pliny though the location on the north side of the Black sea fits in the right region for where Ashkenaz’ descendants might’ve settled.

Josephus says that the Greeks called Ashkenaz’s descendants the Rheginians (see sentence containing, “Of the three sons of Gomer,” here) but the only reference I found to that was a scholar who is listed in the note on Genesis 10:3, here who connected that name to Rhegae, a town south of the Caspian sea.

Various sources link the Scythians to both Ashkenaz, Gomer’s son, and Magog, one of Japheth’s sons mentioned in Genesis 10:2. See the full show note on this subject when addressing Magog later in this episode.

For the Scythians as warriors who controlled regions of the middle east and Greece until being limited to north of the Black sea around Crimea, see here. That source says their culture disappeared around 300 B.C., but Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association suggests they spread into Russia and Siberia. For an overview of the Scythians, see here. For the suggestion that Gomer’s children extended into “Muscovy and Germany” see note on Genesis 10:3 here.

For “Ashkenaz” being a Jewish name for “Germany,” see the notes on Genesis 10:3 here, here, and here with the latter calling the identity of the Germans as descendants of Ashkenaz uncertain, but probably right. This identification stems from the middle ages according to note on Genesis 10:3 here. The article here equates “Ashkenaz” with “Germany” in Hebrew. There’s also a reference in the note on Genesis 10:3, here that the Germans may have been a colony from Ashkenaz based on material found in Diodorus Siculus, a Greek writer from around 2000 years ago, though that article notes that Diodorus isn’t considered reliable.

One commentary, in it’s note on Genesis 10:3 here, also suggests that the name “Scandinavia” could have connection to “Ashkenaz” as well as the word “Saxon” and possibly even the source of the name “Asia.” To me, the “Saxon” link isn’t much of a stretch as they also lived in Germany (see here) where Ashkenaz’s descendants might’ve settled, and Scandinavia is plausible, too, given how close it is to Germany, but this was the only commentary that made these links so it doesn’t appear to be a common identification.

For the Assyrian records from around 1100 BC of “Tapal” or “Tabal” and “Muski” or “Mushku” as allies who tried to conquer Mesopotamia see Horn, S. H. (1979). In The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary (p. 1136). Review and Herald Publishing Association and Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association which contains essentially the same entry. The “Tubal” reference in that source doesn’t make it clear that the inscriptions are Assyrian, but that appears to be the case based on the “Meshech” entry. Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association mentions that the Hittites might’ve called Tubal “Tapala” while and the Assyrians called Tubal “Tapal” and Meshech “Mushku.”

For the descendants of Tubal and Meshech settling in Turkey after their failed invasion of Mesopotamia, see entries for Tubal and Meshech in Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 270–272). Review and Herald Publishing Association. The statement in that entry that this where classical Greek authors came to know about them I assume refers to people like Herodotus who talk about the Tibareni and Moschi as referenced in note on Genesis 10:1 here.

For some reason, the descendants of Tubal and Meschech are linked together, including being listed with one another in Ezekiel 38. Scholars tie “Tubal” to the “Tibareni” and “Meschech” to the “Moschians,” both tribes who lived in the north east part of Turkey. See note on Genesis 10:1-2 here, notes on Genesis 10:2 here, here, and here, note on Genesis 10:3, here and here and Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers. The Bible also mentions them as people who live far away in Isaiah 66:19 and Psalm 120:5 and in note on Genesis 10:2, here

Tubal, whom Josephus calls “Thobel” founded a people known as the “Iberes” according to the sentence beginning “Thobel founded the…” here. At first glance this would appear to be a reference to Spain, and the Iberian peninsula, but there was also a kingdom of the Iberes around what is today Georgia in central Asia. For more, see here. The commentary note on Genesis 10:2, here makes that connection, but the note on Genesis 10:2, here confuses the Iberia of central Asia with the one in Spain. The distinction is pointed out by Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 196). Appendix 3. Kindle Edition. Even so, the note on Genesis 10:3, here suggests that Tubal’s descendants also gave their name to a place in Albania and ultimately may have been the source of the Iberians in Spain, too.

The Moschians lived in northeast Asia Minor as stated in an earlier show note. Josephus also says they lived in Cappadocia which is in central Turkey. Josephus also references a city named Mazaca that used to be the name of their whole nation (see sentence containing, “the Mosocheni were founded,” here. It’s not clear where Mazaca was in Cappadocia, but it could’ve been the same as the home of the Moschians as the reference to Pliny in the note on Genesis 10:3 here refers to the Moschians themselves as being in northeast Cappadocia suggesting that northeast Asia minor and northeast Cappadocia overlapped.

For the suggestion that Tiras went around to the east of the Black Sea and then north, see note on Genesis 10:1-2 here.

For the connection between Tiras and the Turusha, a part of the “Sea Peoples” of Egyptian history, see Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association., Horn, S. H. (1979). In The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary (p. 1125). Review and Herald Publishing Association., and Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association.

For the connection between Tiras and the Taurus mountains, see note on Genesis 10:2, here.

While noting Josephus’ connection between Tiras and Thrace, the note on Genesis 10:2, here says it is more common to point to Tiras’ descendants as pirates in the Aegean sea. The entry in Horn, S. H. (1979). In The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary (p. 1125). Review and Herald Publishing Association says that Herodotus called them the Tursenoi. The note in Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association and it links Tiras to both these pirates in the Aegean and to the Tyrsenians of Italy.

Scholars try to link the Tyrrheni to both Tarshish, Japheth’s grandson through Javan (as I discussed in the last episode) or to Tiras. As far as who the Tyrrheni were, one suggestion points to them as one part of the early inhabitants of Greece, called the “Pelasgians” (see note on Genesis 10:2, here as well as definition of Pelasgians here). Other references place them in Italy rather than in Greece and suggest they might be the forebears of the Etruscans (see note on Genesis 10:2 in Kidner, D. (1967). Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 108–123). Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.). The reference in Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association also mentions the possible link between the Tyrrheni and the Etruscans, but notes that they only settled Italy around 800 BC, leaving ample time for them to have also been in Greece and other places between then and the dispersion from Babel, but this is my speculation. See also Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association that links Tiras to both these pirates in the Aegean and to the Tyrsenians of Italy.

For Josephus’ reference to Tiras, who he calls “Thiras” as the father of the Thracians, see sentence containing, “Thiras also called those whom,” here. Josephus’ link is referenced by the note on Genesis 10:1-2 here, the note on Genesis 10:3, here, and the note on Genesis 10:2 here which also says that this link is part of Jewish tradition. The note on Genesis 10:2, here refers to the Tiras-Thrace connection as “general consent.” It is also supported by the comment on Genesis 10:2, here and mentioned as a possibility by Barker, K. L. (2002) NIV Study Bible. Genesis 10:2, note. Zondervan.

The notes from Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association also mention that Tiras might be connected to “The Taruisha” and therefore linked to ancient Troy, and a reference comes up to the Thracians being involved in the start of the city of Troy here. From a geographic standpoint, this makes sense as it is near to where the Thracians lived and the region of the Tursenoi pirates both of whom scholars suggest were descendants of Tiras (see other show notes). If that is the case, however, it would appear that the city and region of Troy were related to the descendants of Tiras, but the eventual royal family stemmed from Dardanus (if the Greek lore discussed in the last episode is accurate). See also Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 196). Appendix 3. Kindle Edition who makes the potential connection between Troy and Tiras as well as supporting other theories about Tiras’ descendants found in other sources and mentioned earlier.

For a description of the Thracians as “wild and warlike” see here.

For the description of the Thracians as red-haired and blue-eyed according to Xenophanes of Colophon, see pg. 131 here. There is also a reference to that word here as a definition of a word that also means flame-colored and yellowish-red (see also on pg. 1350, lower right, here. For the quote in the original Greek, see on line 10 on pg. 36 here. See also pg. 24 (fragment 16 in Greek) and pg. 90 (discussion of fragment 16) here.

For the geographic limits of Thrace, see the description on pg. 885 here.

For scholars who refer to a river in ancient Thrace as both “Athyras” and “Atyras” and suggest it reflects Tiras’ name, see note on Genesis 10:2 here and note on Genesis 10:3, here. For a reference to the Athyras river being in Thrace and near Byzantium (modern Istanbul), see pg. 310 here. For the Dniester river previously being called the “Tyras” river, see “Dniester” entry on pg. 349 here as well as Strabo here and footnote. For the suggestion that the river was named after Tiras, see pg. 48 here as well as pg. 307 here and pg. 89 here. The city Tiraspol in Moldova was named after the ancient name of the river and, at least in English, is spelled identically to the name Tiras found in Genesis. The modern city was founded in just the last few hundred years, but has a history as an ancient Greek colony (see “Tiraspol” entry here.

In trying to trace the Thracians further through history, there was one northern Thracian tribe known as the “Getae” (see here, though the article here suggests that there was some distinction between them and the Thracians). One commentary (see note on Genesis 10:2, here) suggested that these “Getae” were the ancestors of the Goths and therefore the forefathers of the Scandinavians. Digging into this question, that idea appears to come from Jerome, though Jerome says others had made the link before he did (see pg. 50 here. The later authors Cassiodorus whose work is summarized by Jordanes suggests the history of the Goths is the same as the history of the Getae (see summary of book here. Apparently this link between the Goths and the Getae hasn’t really been supported since the 1950s according to footnote 5 on pg. 231 here. The modern perspective doesn’t have much to offer as an alternative, though, only suggesting that the Getae-Goth link is wrong (see note on “Goth” entry on pg. 272 here. Jordanes claims that the Goths originally came from Scandinavia, but from a Biblical perspective, they would’ve first had to migrate to Scandinavia from Babel (see here and pg. 381 here. In short, we can only confidently trace Tiras as far as the Thracians by means of Josephus, but not further. For a further discussion of the history of connecting the “Getae” to the “Goths” see pgs. 28-29 here.

In the Illiad, the story of the Trojan war (see pg. 568 here), Homer mentions the Thracians as a group involved in the war on the side of the Trojans (see reference on first page of article here as well as the Illiad book 10 here). In the course of the story, Homer refers to “Ares” the Greek god of battle, but Ares wasn’t popular in Greece (see here). His home was actually in Thrace (see pg. 169 here), and he, or some similar god, was one of the main gods of the Thracians (see pg. 455 here which states that “Ares” was popular in Thrace and notes that the planet Mars is named after him). In addition, the term “Thrax” was a synonym for someone from Thrace (see here) and according to pg. 95 here “Thrax” was also a name for Ares. Furthermore, when Homer talks about Ares in the Illiad, he uses the phrase “Thouros Ares” at least a couple of times (see examples in chapter 5 around line 505 in Greek and English and in chapter 24 around line 495 in Greek and English) with one source suggesting it was used 11 times (see here(no page number, search “thouros”)). The phrase is translated in those sources as either “furious Ares” or “wild Ares.” Elsewhere the word “thouros” is translated as “unbridled” and means “violent” or “raging” according to note found here(no page number, search for term “thourios”) but a few scholars from books written in the 1600s, 1700s, and 1800s suggest the phrase “Thouros Ares” is a way of referring to the Thracian god Mars, probably meaning the Thracian god of war, and that “Thouros” is just a version of the name “Tiras” (see footnote 21 on pg. 318 here, pg. 683 here, pg. 88 here with a copy of that material presented by Jonathan Edwards on pg. 702 of the book here). Taking that link a step further, Noah Webster, of Webster’s dictionary fame, suggested that this “Thouros” eventually became “Thor,” the thunder god of Scandinavia, and later, of the Vikings (see pgs. 99-100 here for Webster’s comments and here as well as pg. 90 here for information on Thor). Digging into this idea by searching references to “Thouros,” the name is linked with Mars in a few places. First, in the context of discussing the Germanic god “Tyr,” on pg. 102 of the French paper here that was written in 1872, it refers to the planet Mars as something known in Greek as “thouros” which means “burning” and is very similar to the name of a barbarian god of war (translation provided by Google Translate, though it translated “Mars” as “March.” Given the context of a planet, I assumed “Mars” to be the correct translation). In addition, you find a reference on pg. 1509 here that also says the Greek name for the planet Mars was “Thouros,” a definition confirmed on pg. 413 here. The entry here in Greek for the “god of destruction” gives Ares as an alternate name for Mars. Meanwhile, the idea that “Thouros” was a name is disputed by the entry note on pg. 91 here written and in 1894. The word “thouros” in the Greek-English lexicon appears on pg. 680 here and notes that “thouros” means “rushing, raging, impetuous, and furious” and is always used as an epithet for “Ares,” meaning either a descriptor or an euphemistic term. From all of this, as best I can tell, the idea that “Thouros” in the Illiad is a name for “Tiras” was a relatively common idea from the 1600s to the 1800s, including as a commentary note on Genesis 10:2 here that directly links “Tiras” to “Thuras” and a more generic note that the Thracians worshiped a god named “Thuras” in the note on Genesis 10:2 here. After this period, though, there’s no mention of that theory. I don’t know if the idea was debunked and scholars decided “thouros” was just an adjective used to refer to Ares, or if it disappeared for some other reason. At this point I can’t find anything that either confirms or explains why the theory vanished.

In the same note that discusses “Thuras,” the note on Genesis 10:2 here suggests that Tiras was also worshiped under the name “Odrysus.” This is also mentioned on pg. 683 here and pg. 281 here. How “Odrysus” and “Tiras” are related is explained on pg. 89 here. Researching “Odrysus” it was a Thracian kingdom in the 400s BC according to article here. It is also mentioned as one of the previous names of Hadrianopolis in this entry. Given that the link between “Odrysus” and “Tiras” is supported by the same references that note “Thouros” or “Thuras” and “Tiras,” and that the idea isn’t found more recently, it is likewise an uncertain claim.

I talked about Dardanus as the forefather of the Trojans in the last episode. The reference on pg. 90 here speculates that Tiras might be the forefather of the Trojans given that “Tros” has all the same consonants as “Tiras” (Trs), an idea that is also offered on pg. 702 here (though given the similar language, I think the second source depended on the first one for its information). The legends of Dardanus as the forefather of Tros comes from the Illiad book 20 here(with plenty of mythology mixed in) where Aeneas is speaking.

For background on Snorri Sturluson, see here. For more detail about the Prose Edda and Proetic Edda, the major sources of our knowledge of Norse legends, see later show note.

In the Prose Edda (see full text here) Snorri talks about the history of the world and places the origin of those who became Scandinavians in Troy.

As for why Thor is given by Snorri as the forefather of Odin rather than Odin as the father of Thor, as it is generally described, the author on pgs. 70, 71, and 74 here suggest that there was a shift from Thor being the more important god to Odin, with Odin perhaps being favored by the nobility of the region, leading to a shift of position with Odin becoming the father rather than the son. It is interesting to note, as that author states, that the non-noble people still preferred Thor.

Snorri describes both Thor and Odin as people though they are commonly remembered as Norse gods (see pg. 32 here as well as here and here). Snorri doesn’t say, though, how these people came to be worshiped as gods as stated on pg. 33 here. Another author, Saxo Grammaticus, living near the time of Snorri and writing a history of the Danes, also put forward the idea that the Norse gods were just men but he suggested that there had once been giants, but the second class of men who had mental power (called divination, I assume a reference to magic) defeated the giants and came to be considered gods. Saxo also says that Thor and Odin knew sorcery and came to control people who then thought of them as gods. Saxo doesn’t claim impartiality. In one story where Odin seeks advice from prophets he says that “Godhead that is incomplete is often in need of human help,” making it clear that if Odin were a real god, he wouldn’t need human advice. For this detail and others about Saxo and his history, see pgs. 34-36 here. For a summary of Snorri and Saxo’s claims, see pg. 36 here where the author sums up their position by noting that either magical power or some other ability allowed people like Odin and Thor to make others worship them as gods. This could be another example of famous ancestors eventually being worshiped as gods (see earlier episodes in the Grandfathers of History series for other examples), though Snorri’s record comes after Christianity had already spread to Iceland (see article here for Snorri writing in the 1200s when Iceland became Christian closer to 1000 AD) so Snorri may have been undermining Norse mythology because of his belief in Christianity.

For the history of Odin as a man according to the legend found in the early part of Snorri’s Ynglinga-saga at the start of the Heimskringla, see summary on pgs. 33-34 here. For the original text of the Yngling-saga of the Heimskringla in English, see here with part 10 denoting Odin’s death. Why this history has Odin giving land to Thor (see section 6 in link above) rather than Odin as Thor’s descendant as stated in the Prologue in the Prose Edda (see pg. 7 here also written by Snorri is unclear unless Snorri was simply reporting different legends (though that’s only my speculation). In either case, the origin of the “god” is given as an ancient heroic man. Another reference to Thor as Odin’s son is found on pg. 65 here.

Though some might say that the beginning of the Prose Edda that describes Thor and Odin as people rather than gods might’ve been written by someone other than Snorri, this doesn’t appear to be the case since later in the book Snorri tells his readers not to believe the stories of the gods other than as described at the start of the book. In other words, he tells them not to believe in the gods other than as a memory of ancient people. (see pg. 31 here). The author of the above reference thinks this is just an example of euhemerism rather than necessarily accurate, a position echoed here. The author also notes that for hundreds of years it was common to argue that pagan gods were memories of men who were aided by demons or magic as mentioned on pg. 31 here. It is argued on pg. 59 here that this section of Snorri’s work might be invented as an attempt to give the Scandinavians their own version of the Roman Aeneas. For more on Aeneas, see Episode 18.

Though it is, perhaps, a tenuous link, it is interesting to me that both Thor and the Thracians are described as having red hair with references that come from different sources. This makes me lean toward the conclusion that they were related, though that is simply my speculation. For Thor having red hair see pg. 161 here and for a red beard, see pg. 172 here and pg. 80 here. I couldn’t find whether this description of Thor was based on Snorri’s comments or another Norse mythology source that talks about Thor, but even if Snorri was the source (and therefore a potentially Christian influenced source) he would still have needed access to some ancient reference to Xenophanes, or another now-lost writer, (which I doubt he had) who knew that the Thracians were described as having red hair (see earlier show note) in order to accurately “make up” his history of Thor with that description. As such, I think that Thor with red hair and the Thracians having red hair are independent references. Whether this means that the Thracians were related to the Scandinavians is an open question, though, as tribal mixing and long time frames are involved, leaving lots of opportunities for the genes for red hair to sneak into any people group.

As an additional interesting note, Snorri also suggests that the Aesir, as the collection of Norse gods was called, really means “men of Asia.” on pg. 32 here.

The reference to pagan gods as once human is not a new idea. There are sources from the early Christian era that also suggest that the Greek gods, too, were originally only human. One source is Lactantius who wrote around 300 AD. The article above mentions that Lactantius was less a good Christian theologian and better at debunking paganism (see a similar idea on pgs. 23-25 here. For some of his undermining of paganism, see pgs. 48-49 here where he mentions Euhemerus and pgs. 51-54 here where he discusses Jupiter and Saturn as actual humans. Anobius, another writer from the same era, argued that the heathen gods couldn’t be God because they are represented as having been born (i.e. didn’t always exist). Arnobius was once a teacher of Lactantius (see pg. xi here when both men were still adherents of paganism and both converted separately (for Arnobius’ comment, see here). An even earlier reference comes from Tertullian (see Encyclopedia of Religion entry here) around 200 AD who refers to the ancient authors always talking about Saturn as a man, not a god (see pg. 36 here).

Genesis lists three sons of Gomer, but it doesn’t say that those were his only sons. Perhaps they were the first sons, or the most well known early in history. It could also be that the descendants who went by some version of Gomer did it even though they were descended through one of the three sons Genesis names, but this is all my speculation.

The note on Genesis 10:2, here refers to descendants of Gomer living in Pontus in Asia Minor, a region along the coast of the Black Sea according to information here. The note on Genesis 10:2, here, talks about them being on the shores of the Black and Caspian seas. The note on Genesis 10:2, here, says they lived between Madai and Scythia, which would probably sandwich them between the Medes (see later in episode) to the south and east and the Scythians in Ukraine and Russia. This fits with Ezekiel 38:6 that puts Gomer and his son Togarmah to the north (see note on Genesis 10:2, here). I say that “some” of Gomer’s kids traveled north, as there is a reference in Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers that the descendants of Gomer were driven out of their homes in the 7th century BC by the Scythians and fled into western Asia Minor before being pushed out of there. This suggests to me that while some traveled north as supported by show note details below, if Easton’s comment is correct, some must’ve stayed behind until the Scythian invasion hundreds of years later. For more on the Scythian-Cimmerian conflict, see note here.

For Sargon’s reference to the descendants of Gomer as the “gimirraia” or “gimarraja” see Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 169). Pacific Press Publishing Association. For reference to “Gamir” or Gimirrai” see Horn, S. H. (1979). In The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary (p. 428). Review and Herald Publishing Association and Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association. That commentary also suggested that there was a region in Armenia named “Gamir” today, but I couldn’t find references to it in a brief search of the map.

For various commentaries connecting the descendants of Japheth’s son Gomer to the Cimmerians, see note on Genesis 10:2, here (which also attributes the name of the Crimean peninsula to them), note on Genesis 10:5 here, and note on Genesis 10:2, here. See also Barker, K. L. (2002) NIV Study Bible. Genesis 10:2, note. Zondervan who affirms that Gomer’s children became the Cimmerians and Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers, as well as see Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association. In addition to the Cimmerians giving their name to Crimea, what is today known as the “Kerch strait” on one side of Crimea used to be called the Cimmerian Bosporus according to the article here.

For the descendants of Gomer being connected to the Kimbri of Germany, see note on Genesis 10:1-2 here. The note on Genesis 10:2 here connects Denmark to the Cimbri and points out that Jutland had the name “Chersonesus Cimbrica,” something mentioned here also. See also note on Genesis 10:2, here and Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Connecting the descendants of Gomer to settlers in France, Spain, and Britain, see note on Genesis 10:1-2 here which says the descendants of Gomer in Britain called them selves the Kymry, Cambri, and Cumbri. The first page of part 1 of the book here suggests, with footnote references on that page, that it is generally believed that the Welsh descendants of Gomer came to Britain from France about 300 years after the Flood. The note on Genesis 10:2 here says the Welsh called themselves the Cumery, Cymro, and Cumeri as late as the mid 1700s when that commentary was written (see when commentary was written on pg. 21 here). Further support can be found in note on Genesis 10:2, here. See also note on Genesis 10:2, here and Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers. While ancient authors don’t call the inhabitants of Britain or Ireland “celts” we know that they spoke a similar language to people living on the continent according to the note on pg. 586 here.

For the descendants of Gomer generally being considered the Celts, see note on Genesis 10:1-2 here and note on Genesis 10:2, here. See also Easton, M. G. (1893). In Easton’s Bible dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers. The note on Genesis 10:3, here identifies the descendants of Riphath as the Celts, though it is unclear whether only the descendants of Riphath became the Celts or if there are many branches of Gomer’s descendants (both through the sons Genesis names, and perhaps others it doesn’t name, if any) who called themselves Celts.

Julius Caesar notes that the people in Gaul referred to themselves as “Celts” (see pg. 585 here).

According to the note on Genesis 10:2, here, Josephus suggests that the the "Galatians” used to be called “Gomerites” (see sentence containing, “For Gomer founded,” here). It is suggested in the article here that the Galatians were later invaders who came down from Gaul in the 3rd century B.C. If the name “Galatia” is connected to Gomer, and Gomer is the forefather of the Celts, then these settlers of Galatia in the 3rd century B.C. would be descendants of Gomer, even if they went all the way through Europe and 2000 years of history before returning to Asia minor and settling there.

I use the title “English channel” even though “English” comes from “England” which is named after the Angles (see here). who hadn’t showed up in history yet.

For an overview of the region people think used to be above sea level between Britain and the rest of Europe, see here and here which also mentions some artifacts that have been found. See also the article here that talks about carved bones that have been found and here that talks about stumps and other artifacts.

The best summary reconstruction I’ve seen of a creation-supporting understanding of the environment and climate after the Flood is found here. To me, it is a theory that offers a well-reasoned explanation for how the ice age evidence fits both physics and a Biblical time line. For other useful articles, see here, here, and here for a discussion of the effects of volcanoes during and after the Flood as well as the theory of impacts from things like meteors and asteroids. For other articles on the topic, see here, here, here, and here. For ongoing challenges for creation-supporting theories of the physics of the Flood, see here.

For a previous discussion of volcanoes and the Flood, see Episode 13.

For more on Tambora, see show notes on Episode 1. To compare the size of the Toba eruption compared to 1815’s Tambora eruption I used the amount of ash emitted. Tambora emitted an estimated 36 cubic miles (see here) and Toba an estimated 670 cubic miles of debris (see here) making Toba about 18 times larger. The article here suggests that Toba, “produced over 50 times the stratospheric aerosols as Tambora.” For another reference to Toba, from a non-Biblical viewpoint, see here and here.

For the definition of a glacier, see here.

For an “ice age” defined as extensive glaciers, see here.

The debate over the end of the land link connecting Britain with the rest of Europe depends on whether you follow a model that accepts the long ages proposed by secular researchers or one given by those who accept the time line of history given in the Bible. Assuming the Bible time line to be correct, as best I can understand from the various articles (see earlier show note), the land link between Britain and the rest of Europe was either present until the end of the Ice Age when it was flooded or destroyed or it was flooded by the ocean until the ice build-up from the Ice Age lowered sea level enough to expose it before being re-flooded and finally eroded away at the end of the ice age. For a discussion of models about how the land linking Britain and Europe was ultimately submerged, see here and here. For the suggestion that it was due to a flood of water from a North Sea lake during the Ice Age, see here. For the comment that the low-lying land connection was only briefly accessible when the Ice Age had removed enough water to lower sea level, see here, and for the suggestion that the Flood of Noah’s day did most of the work but the canyon formed at the English channel was blocked by debris until being finally formed at the end of the Ice Age, see here. I don’t put particular emphasis on any of the mechanisms, only that there appears to have been a land link between Britain and the rest of Europe, and that the ocean destroyed it at some point.

For hippos found in Leeds in the middle of Britain, see here. For a news article from 2004 mentioning the larger size of a hippo found near Norfolk, see here. For more, see pgs. 797-799 here. There is also the mention of hippo remains found at 3 more sites on pg. 235 here with what appears to be a reference to 4 different sites in the table on pg. 237 at that reference. Pg. 240-241 refers to “numerous” examples of hippo remains found in England and Wales and describes how the climate must have been warmer. In addition, pg. 279 here notes how warm it would need to be for animals like the hippo to survive in England. For a Biblical perspective explaining hippos in England, see the articles here and here.

To be clear, the idea that some of Gomer’s descendants may have crossed to the modern island of Britain via Doggerland before it submerged when the Ice Age ended and sea levels rose is my speculation. Those descendants may have come by boat rather than by land even when it was a peninsula or they may have come after the English Channel formed rather than migrating across on dry land.

Earlier, I mentioned that some scholars identify Ashkenaz’s descendants as the Scythians. See, for instance, note on Genesis 10:3 in Kidner, D. (1967). Genesis: An Introduction and Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 108–123). Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press., Barker, K. L. (2002) NIV Study Bible. Genesis 10:3, note. Zondervan., and Doukhan, J. B. (2016). Seventh-day Adventist International Bible Commentary (pg. 170). Pacific Press Publishing Association. There is some dispute, though, since Josephus suggests the Scythians were the descendants of Magog (see sentence beginning, “Magog founded those that…” here, another of Japheth’s sons that Genesis mentions. Other sources supporting this Scythian connection to Magog include notes on Genesis 10:2, here, here and here that links Magog’s descendants to both a northern tribe and notes the common connection to the Scythians, and note on Genesis 10:3, here. It’s possible both of these theories are true. The Scythians could be descended from both Ashkenaz and Magog’s descendants. Cooper notes that there is evidence connecting Ashkenaz to the Scythians and suggests that Magog’s descendants might’ve been absorbed and combined with Ashkenaz’s children (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 194). Appendix 3. Kindle Edition.). This fits with the comment from Nichol, F. D. (Ed.). (1978). The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 1, pp. 261–291). Review and Herald Publishing Association suggesting that Magog’s children may have lived north of the Black Sea near Gomer’s children, but noting that identification of Magog’s descendants is challenging. From my perspective, at some point the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth didn’t maintain perfect tribal distinctions but would’ve begun to blend, so it is possible that the Scythians were descendants of both Magog and Ashkenaz as Cooper suggests and that the descendants of Magog were absorbed into the tribe of Ashkenaz’s children since the connection between the Scythians and Ashkenaz is more certain according to Cooper (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 194). Appendix 3. Kindle Edition). This also fits with the comment on pg. 526 here which refers to the Scythians as having a blended ancestry. For notes on another possible branch of Magog’s family, see the next episode.

For the etymology tying “Scythian” to “Scot” through Greek, Welsh, and Saxon, see pg. 1112 here. That’s from an edition of the book written in 1898. A later edition, on pg. 990 here, makes no mention of that etymology though I don’t know if this is because the history fell out of favor or just due to condensing the material found in the book. Oddly enough, the pathway for the Scots from Scythia to Scotland appears to have gone through Ireland, with them only moving into Scotland around 500 AD (see here). For the timing of the Saxon invasion of the island of Britain, see here and here. For the island being named “Britain” see here.

For the Declaration of Arbroath that describes the Scottish nobility making a claim of independence from the English, see here. For the actual text and translation, see here where it describes their migration from “Greater Scythia.” The Scots say they came to Scotland “twelve-hundred years after the people of Israel crossed the Red Sea.” Assuming the Red Sea crossing occurred in 1491 BC (see Ussher, James (2006-11-01). The Annals of the World (Kindle Locations 1338-1345). Master Books. Kindle Edition.) that would place their arrival in Scotland about 300 BC, or around 1600 years before the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. Also, on pg. 126 here it mentions that the Scots are believed to have been an offshoot colony of Ireland. Interestingly enough, the Declaration of Arbroath also says they came via Spain and DNA testing recently suggested that the Irish are most closely linked with people from northern Spain (see here).

The written records of European history we have from the middle ages may be accurate copies of earlier documents, but without those earlier documents or another method of independently verifying the accuracy of the documents we do have, the existing records are open to the accusation that they were modified to a greater or lesser degree by Christians or other parties rather than a faithful record of what was known at the time. It is not so much that these records are wrong, just that they cannot be verified.

For Elysium as something found in the myths of Ireland and Wales but isn’t in evidence among the Celts who lived on mainland Europe though it probably existed there, too, see pg. 362 here.

For Elysium being known for a lack of death and food of youthfulness, see pgs. 376-378 here. For fruit being the most common food that gave immortality, see pg. 378.

For the Elysium having impressive trees with branches of silver and apples of gold, see pg. 380 here.

For reference to a Rowan tree guarded by a dragon and the Rowan berries healing wounds and lengthening life, see pg. 377 here. See also pg. 35 here. For a paraphrase and translation of the original story, see pgs 36-38 here.

For other foods of immortality in Celtic lore, see pg. 158-159 here as referenced from pg. 180 here.

In Celtic legend, there is also the story of the theft of apples of Hisberna as referenced on pg. 339 here citing pg. 186 here which ultimately refers to pg. 58 and 63 here. On pg. 58, the “Garden of Hisberna” is footnoted to be the same as the “Garden of the Hesperides” which makes it appear that the story in question is influenced by Greek myth rather than an independent Celtic story, even if there are different elements.

There is also reference to a Celtic paradise of Avalon where a hazel tree grew nuts that gods and certain humans ate to maintain life, as referenced on pg. 34 here. The article here suggests that this “Avalon” might be linked rather than independent of the idea of Elysium.

For the Welsh story of the Flood, see pg. 175 here. See also pgw. 256-257 here. For the age of manuscripts with this story dating back less than 1000 years, see later show note. The note on the bottom of page 176 here suggests the story might be related to the Bible.

The most complete information we have for the legends and myths of Scandinavia are the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda (see here). The Prose Edda was written around 1220 by Snorri Sturluson, referenced earlier when talking about Japheth’s son Tiras. Snorri was a historian and leader in Iceland and the Prose Edda was a textbook to help would-be poets understand the metaphors used in Norse poetry (see here as well as pg. 5 here). The Poetic Edda is a collection of poems that were probably composed between 800 and 1200 AD with many of them likely before 1000 AD. (see pgs. 7-8 at above reference, also note here gives 800 - 1100 AD). Christianity really only spread to Iceland between 1000 - 1200 AD (see pg. 8 at above reference) but the copies of the poems we have come from the 1300s AD (also on pg. 8) meaning that the Prose Edda and the version of the Poetic Edda we have were either written or copied down after Christianity was already present in the region. As such, we cannot know for certain whether the mythology and stories given in the Eddas offer an accurate version of Scandinavian pagan beliefs or whether those stories they tell have been influenced by Christianity. I tend to think that much of the folklore is genuine Scandinavian belief from before Christian influence, but that is only my non-expert opinion. For a good overview of the sources and timeline, see the introduction to the book here.

For the outline of the Norse creation story, see pgs. 324 - 325 here. It is unclear how there is a “north” or “south” to this “chasm” or “abyss” and the the author similarly comments that it is unclear who made the things in the north, but such is the legend. The author also suggests that the warm air that formed the life might be a sign of Christian influence, but that is their speculation.

For the ice melting and forming a cow who sent rivers or streams of milk from its udders, see pgs. 324-325 here. Four there being four rivers of milk see section IV-6 here. It’s also compared to the four rivers flowing in Eden in Genesis 2:10-14 see pg. 256 here which comes from a source specifically outlining parallels between Genesis and world mythologies and is therefore open to the accusation of bias, as am I.

It’s interesting to note from pg. 201 here that the Norse belief in night coming before day, something also believed by the Celts, suggested that the world began in darkness rather than light, just as it is stated in Genesis 1:2-3. Furthermore, the author of that source suggests this is accurate mythology implying that is an idea that doesn’t appear to be due to Christian influence.

There are also references to the idea of the earth rising out of an ocean mentioned on pg. 325 here, though that wasn’t obvious to me from the stanza the author refers to. They say that the legend goes on to talk about how the sun, moon, and stars were given their places and how the gods gave some names, events that have some parallels in Genesis.

Odin was also considered the creator of the first man and woman as well as the heaven, earth, and everything in it, though his originator role could be due to Christian influence as speculated by the author on pgs. 61 and 326 (Odin as creator) and 63 (speculation on Christian influence on Odin) here. Perhaps this would imply that as adherents of Odin came to understand Christianity, they wanted their chief god to have the same accomplishments as the Christian God, but that is just my speculation.

As pointed out by other authors regarding worship of the gods in the Roman and Greek religion, Odin, too, was born at some point and therefore couldn’t be the same as the All-Powerful God of Christianity. For reference to Odin’s birth, see pg. 63 here.

I didn’t say anything about the creation of humans according to Norse mythology in the audio, as there’s at least three versions of it. In the first two Odin and two others find either “Ash” and “Elm” or “two trees” that they shape into human beings and give various abilities to including soul, sense, heat and good color, hearing and sight, and life (for these versions, see pg. 327 here). In another version, humans are the sons of Heimdall, the god who guarded the rainbow bridge between heaven and earth, according to pg. 155 at the above source. For more on the rainbow bridge, see later show notes.

On pg. 328 here it is also mentioned that the Germans had a god who came from the earth and that the god and his son were the start of the Germans which the author suggests is similar to the giant in Norse mythology who gave birth to other giants without a woman.

For the common belief in a tree that reached to heaven among various mythologies, see pgs. 334-335 here including reference to the Norse tree having a number of similarities to this common belief. For details of the tree itself where the gods gathered every day in judgment after crossing the rainbow bridge, see pg. 23 of the above source. That page also mentions a well under the roots of the tree and pgs. 49 and 167-168 make it clear that knowledge, wisdom, and understanding were found in the well. On pg. 336 that author suggests that, despite the similarities, Yggdrasil is not derived from Christianity, though he allows that some details may be due to Christian influence. For the Yggdrasil tree being large, see here.

For the Norse gods not being immortal but having to eat apples supplied by the goddess Idunn to stay young, see pg. 22 and pg. 178: here

The name of the goddess who carried the apples of youth was Idunn. It is suggested on pg. 178 here that her name meant “renewal” or “restoration of youth.”

It’s argued that since apples were not present in Iceland and only came to Norway later when grown in the gardens of monasteries that details from the Bible have worked themselves into the story of Idunn and the apples, but the author on pg. 180 here suggests that neither the Biblical details or stories from Greece or Ireland explain the story fully and suggests that it was an original story, though it was perhaps influenced by outside sources.

For the giants coming before the gods see pgs. 324 - 325 here (Also see that Odin was descended from giants according to pg. 278 in the same reference). That source on pg. 281 also notes that there are various theories about who the giants were including earlier less civilized men who used stone tools or gods from a previous religion that the worship of Odin and other Norse gods replaced, but the author admits that these theories don’t fully work. I wonder if there is a parallel between the giants in Norse legend and the people who lived before the Flood in Genesis (see “men of renown” in Genesis 6:4) with the forefathers of the people who lived in northern Europe coming after these ancient “giants” and taking their place in people’s memories and affections, but this is just my speculation.

For the cow’s continued licking producing another being who became the grandfather of Odin, Vili, and Ve, see pgs. 324 - 325: here and pg. 256 here where the cow licks either ice or stones.

For Odin, Vili, and Ve killing Ymir, the giant formed from ice, and flooding the world with Ymir’s blood as well as the survival of only one giant and his wife or household on either a boat or a millstone, see pgs. 275-276 and 324 - 325: here and pg. 256 here. See also section IV-7 in the Prose Edda here and pg. 11 here. For the translation given on pg. 35 here it defines the boat as a hollow tree trunk with a word that can also mean coffin (see footnote on that page). The comment on pg. 92 here says that the word used for “boat” is uncommon and could also be translated “cradle.”

For heaven and earth being linked by a rainbow bridge, see note on Genesis 9:13, here. See also pg. 153: here. According to the Norse legend, the rainbow as made of only three colors (see pg. 329). The gods crossed the bridge each day for judgment at the well of wisdom under the Yggdrasil tree (see earlier show note) with the bridge only being broken down when all the gods are destroyed (see pg. 329 here).

Based on a comment on pg. 336: here, there was evidently a mountain in heaven at the other end of the rainbow bridge.

Christian beliefs did not completely replace beliefs in the old Norse gods even after Christianity spread to Scandinavia. In one passage, the author mentions someone named “Helgi the Thin” who was a Christian, but still ask guidance from Thor when traveling at sea. See pg. 75 here. The author references the “Landnamabok” for this story, which describes the settlement of Iceland in the 800s-900s showing that Christian influence was in place well before Snorri wrote the Prose Edda, even if Norse religion was also present. For more on “Landnamabok” see here.

For the origin of the names of the days of the week, see Tuesday coming from the god Tyr on pg 97 here, Wednesday referring to Woden on pg. 19 here (which also mentions Woden and Odin as two names referring to the same god), Thursday referring to the god Thor as mentioned on pg. 68 and 177 here and Friday coming from the name of the godess Frigg on pgs. 176-177 here. As for the other three days of the week, they come from Rome. Saturday is named for Saturn, the chief god of the Romans. Sunday is named in honor of the sun, and Monday is named to honor to moon as mentioned here.

Regarding dwarves, legends in Denmark suggest that trolls are related to dwarves and links them to the angels who rebelled against God and were thrown out of heaven (see pg. 286 here). I think it is safe to suggest that this legend demonstrates at least some level of Christian mixing in native folklore, perhaps with people trying to figure out how the stories of the new Christian religion fit with their previous beliefs and stories.

The Norse religion believed in the destruction of the gods at some point in the future, with the idea of the end of the world coming through water and fire existing among the Celts and in Ireland as well and not due to Christian influence according to pg. 342 here. On the other hand, the author suggests on pg. 344 that the refreshing of the world into a new world likely involves at least some elements from Christianity especially citing a “Mighty one” as an example.

For the legend of the flood from Lithuania, see pg. 93 here and pg. 176 here though it is noted in the footnote on pg. 176 that there is some suspicion about whether the legend is authentic.

For the story of the Flood from Transylvania, see pgs. 177-178 here.

For the story the Voguls of the Ural mountains tell of giants who survived a flood on hollowed out tree boats, see pgs. 93-94 here and pgs. 178-179 here. For the location of the Ural mountains, see here.

There are also references at the start of the Georgian Chronicle, pg. 13 here, that describe how Georgia was founded by Targamos the grandson of Japheth with other references to a tower in Babylon and the division of languages. While the introduction to the book suggests it was originally written in the 1000s-1100s AD (see pg. 7), the oldest manuscripts only go back to the 1500s or 1600s (see Foreward, pgs. 5-10), which is over 1000 years after Christianity spread to Georgia according to article here.

The author argues on pg. 363 here that the idea of Elysium existed in Celtic thought before the influence of Christianity.

For the date of the manuscript that gives most of the details we have on the Celtic paradise of Elysium, see pg. 388 here.

For reference to the burial mounts in Celtic religion being the location of gods later thought to be men (author uses “euhemerized” to describe them) see pg. 78 here. In addition, on pgs. 17-18 here the author suggests that stories that treat the Celtic gods as human is because they were modified by Christian influence. That said, while that author argues the gods were once immortal, it notes, paradoxically, that the myths also talk about their death.

Rather than suggesting a memory of Eden in the topic of immortal food, on pg. 378 here the author argues the concept of food of immortality was simply an extension of the idea that regular food gave life, so divine food must give eternal life

For the Welsh story of the Flood, see pg. 175 here. It also is mentioned in summary on pg. 441 here where it is noted that the story only goes back in our present copies to the 13th or 14th century, but it is likely much older and does not show evidence of being copied from the Genesis account. See also pg. 256-257 here.

For the fact that Snorri Sturluson was a Christian, see pg. 31 here.

Some scholars also claim that the Norse religion was influenced by Judaism and Christianity due to contact between people in the far north and Christian influences on the British Isles as stated on pg. 8 here.

For the legends from Lithuania, Southeastern Europe, and the Ural mountains, I couldn’t find references to how old they were. This could be because they are based on oral tradition rather than a manuscript, but that is just my speculation. In any case, I think it is likely that the copy we have doesn’t go back prior to the arrival of Christianity in the region, leaving those stories also open to the claim that any similarities with the history in Genesis are just due to Christian influence.

The observation that the agreement among genealogies from Britain and Iceland is a valuable evidence of the common history of the nations that inhabited those countries come from Bill Cooper in his book “After the Flood.” In supporting that claim, Cooper compiles genealogies from a number of sources. Evaluating those references, the sources come from some time in the middle ages which place them after Christian influence had spread to the region. They might be copies of older documents, but we cannot prove that without the original, so each of those sources are open to the claim of forgery or modification by Christians attempting to show that their family trees were somehow in agreement with the history in Genesis rather than an independent memory of that history Genesis records. This doesn’t mean these claims are true, only that the documents we have are not old enough to prove otherwise. That said, these documents do show some agreement… but not perfect agreement, and the question becomes, how likely was this level of similarity among kingdoms who were separated from one another and often at odds? For specifics, see Cooper’s book, “After the Flood,” specifically chapters 3, and 6-8.

For the a record of names from Iceland referencing Noah, see pg. 56 here. For an Anglo-Saxon reference to Noah, see pg. 239 here.

For the suggestion that the name “Sceaf” was an invented forefather of the Anglo-Saxons, and that he only shows up in king lists around 855 AD in England, and is therefore a forgery, see pg. 18 and 21 here. That page suggests that while Sceaf probably had some history as a traditional ancestor, he was only connected to Noah as a son born on Noah’s ark during the Anglo-Saxon king Alfred’s rule. In that same source, on pg. 26, it argues that Sceaf was invented as a way of strengthening the rulers of the West Saxons when it was the main alternative power to the Vikings in England.

For the suggestion that the Icelandic king lists copied from lists found in England, see pg. 58 here. See the same idea on pg. 18 of the article here that suggests that “Sceaf” as an ancestor wasn’t known in Scandinavia until the idea migrated there from England.

For the kings in at least the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England gaining their claim to royal power because of their list of ancestors, see pgs. 13 and 17 here where it points out that the king’s family history intended to show that they were descended from a god or former ruler. Later, on pg. 27, it adds that most of the old names in the king’s genealogy were brought into the list from mainland legends as a way to improve the claim to a right to rule by Anglo-Saxon kings who said they were descended from this list of ancestors. Another author, on pgs. 28 and 31 here suggests that it wasn’t how far back a family tree went that mattered, instead it was that you could show you were descended from a god and that you specifically knew the names of your ancestors, an idea also mentioned on pgs. 32-33 here. This is, presumably, in contrast to the populace in general who couldn’t trace their family tree so clearly. The Anglo-Saxons had Woden as a god during some of their history (see pg. 20 here and you see his name in their king lists (such as pg. 239 here). In fact, when the Saxons came to England in the 400s AD, Woden was their most important god and on continental Europe in the 700s AD, Woden was one of the gods that the Saxons had to renounce when they wanted to be baptized as a Christian (see pgs. 18, 38, and 68 here. According to pgs. 23-24 here, the author suggests that when the Anglo-Saxons converted to Christianity they turned their gods into men (the author noting that the Welsh and Icelandic people did the same thing). As such, while Woden, a former god, was still kept as an ancestor in seven of the eight royal family trees in England, they speculate (pg. 36) that extending that family tree was important in order to find a new god to have as the king’s forefather. Combine this with the comment on pgs. 17-18 here that the long genealogy lists were just an invention to link the king back to Biblical history, and there is a motive for a king altering the family genealogy. Whether this was easy to do is a different question. For the importance of family trees in Ireland, see later show note regarding how the genealogies were recorded and checked frequently.

On pg. 21 of the article here the author also suggests some bias in his method, making the fundamental assumption that people generally didn’t remember their ancestors and quoting a rule-of-thumb that shorter lists of ancestors are older than longer lists since people only added names to their genealogies as time went on but were unlikely to forget a name once they had it. One could also make the opposite claim, that names were forgotten as time went on and the older lists remember people further back, but that is my speculation. As for evidence, it is unclear where the belief in invented ancestors comes from other than scholars theorizing.

Among Anglo-Saxon genealogies in England, there is a name “Sceaf” who is given as a son of Noah born on the ark (see the genealogy with the spelling “Sceafing” on pg. 239 here). The article here argues on pg. 18 that “Sceaf,” mentioned as a son of Noah, is an invention of the West Saxons around 900 AD as a way to link themselves with Adam. There are some issues with this theory. The same author, on pg. 45 notes that Anglo-Saxon Christians generally believed that Noah was a real historical person, and on pgs. 14-15, he says that the Christian Anglo-Saxons knew that everyone was descended from Noah, and later in the same paragraph, the author points out that church scholars had divided the world up between Noah’s sons with Ham getting Africa, Shem gaining Asia, and Japheth controlling Europe (see pg. 15 of article above, as well as reference to Bede in footnote 8 on that page, showing that this belief was something present in Britain, not only on continental Europe). Whether or not this idea as to which son inherited which continent was true, that was evidently a belief at the time. Taking this into account, the idea that the Anglo-Saxons “invented” a fourth son of Noah and then claimed to be his descendant as a way to prove their right to rule is doesn’t make sense to me. The same article that puts forth that theory admits, on pg. 27 and 36-42 here, that the Anglo-Saxons knew that the Bible said Noah only had three sons and that they were descended from Japheth. The author mentions someone’s proposed inspiration for a fourth son (see pg. 28) then admits that the idea isn’t convincing and goes on to note (on pg. 29) that this was a contradiction to the belief that Anglo-Saxons were descended from Japheth, a son that the Bible does mention. The author then goes on (in pgs. 30-32) to imply that Sceaf was still this invented fourth son. Comments on pg. 33 note that a legitimate line of descent was important, but doesn’t explain why the “invented” list of ancestors didn’t just go back to Japheth while admitting that the rulers of other places in Europe (mentioning Wales and France) accepted that they were descended from Japheth. Cooper makes this point, too, where he notes that if the genealogy was invented, why would the forgers use a name (like “Sceaf”) that no one knew (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 78). Chapter 6. Kindle Edition. Cooper makes the same argument regarding “Seskef” used in the Icelandic list in Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 89). Chapter 7. Kindle Edition). The author of the earlier article, on pgs. 34-35, suggests that the link to Sceaf was to show that the Anglo-Saxons were “privileged” because they were descended from a son of Noah born on the ark and therefore had a unique relationship to Noah, but, at least to me, this isn’t a good argument. It’s only my opinion, but why would a king “invent” an extra son of Noah then claim to be descended from him if the general belief was that the Anglo-Saxons were descended from a different son? Wouldn’t this simply de-legitimize the king in the eyes of the populace, including competitors for the throne, since the king had just announced that he wasn’t really from the same family and therefore shouldn’t have the right to rule? Not only that, but Japheth would’ve been the older son, making any claims of inheritance by “Sceaf’s” descendants of lesser value. In a broader sense, the king would also have claimed that the whole nation wasn’t descended from Japheth, but from this fourth son instead, removing the whole nation from the blessing given to Japheth by Noah in Genesis 9:27 and, if Europe was given to Japheth kids (as mentioned earlier) then Anglo-Saxons claim to be descended from a different son of Noah would remove their claim to rule part of Europe. To me, the idea of inventing a fourth son doesn’t have a clear benefit and has many potential drawbacks. Instead, I’m inclined to believe that “Sceaf” was the name of a remembered ancestor, and either this “Sceaf” was a corruption of the name “Japheth” as some speculate (see later show note), or it was the name of a later descendant of Japheth (as Snorri Sturluson may suggest, see later show note mentioning “Seskef”). Moving past the name and to why these legends remember Sceaf as having been born on the ark, I wonder if it either a corrupted memory, or or the wording has been muddle (i.e. originally “who was borne (as in carried) upon the ark”), but that is purely my speculation. Regarding the “fourth son” idea on its own, Genesis 9:19 makes it clear that there were three sons of Noah, and from these sons the world was populated, leaving no room for extra sons that Genesis doesn’t mention. For other references that suggest “Sceaf” was a fourth son of Noah born on the Ark, see pg 306 here and pg. 25 here (though stating that Bede makes it clear the Anglo-Saxons were descendants of Japheth).

One of the records we have of the family tree list uses the name “Seth” rather than “Sceaf” as mentioned on pgs. 25-26 here. In that section the author refers to another scholar named “Sisam.” Cooper discusses Sisam as well and suggests a link between the last syllable of “Japheth” and “seth” quoting Sisam as speculating about a possible connection (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 77). Chapter 6. Kindle Edition. To see part of the original quote Cooper references, see the snippet on pg. 316 here. The author of the main paper dismisses the idea that this “Seth” was meant to be a reference to Shem and notes that the Anglo-Saxons wouldn’t connect themselves to Shem, but to Japheth, and suggests that it was confusion on the part of Asser, the author of this genealogical list, who didn’t know who “Sceaf” was. The author suggests (pg. 26) that most copies of the list use the name “Sceaf,” and moves past any significance to the name “Seth,” though he does note that another Anglo-Saxon kingdom named “Scyf” as the ancestor and made him the son of Shem, though he argues that list is a muddled copy of the main list that mentions “Sceaf.”

See earlier comment in introduction to “forging” idea. Copied below in italics:

As far as the lists being similar between Iceland1. and the Anglo-Saxons, while some scholars argue that Iceland copied English lists (see earlier show note), Cooper notes that the lists come from places that are separated from one another both geographically (far apart) and politically (in power struggles against one another) as mentioned in Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (pp. 73, 87-88). Chapters 6,7. Kindle Edition). It’s also worth noting, that any country that might be an accomplice in forging a fake genealogy could just as easily choose to disagree and undermine that new genealogy to weaken the neighboring ruler’s hold on power.

Though there are a number of similarities between the genealogies we have from Britain and Iceland there are also some differences. Cooper lays out a number of genealogies in table form and discusses some of these differences in his book, “After the Flood.” In chapter 7, Cooper gives parallel lists of ancestors offered by both the Anglo-Saxons and writers in Iceland showing that the lists have a similar sequence of names though the names are spelled in different ways and they have different gaps in the lists. For Anglo-Saxon king lists, you can find versions on pg. 239 here with claims that it was written in 855 AD and on pgs. 169-173 here which gives a manuscript age of about 900 AD for a list of Saxon kings, with pg. 173 listing “Scef” as Noah’s son (this second source was referenced by Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 79). Chapter 6. Kindle Edition). These manuscripts are dated after the Anglo-Saxon rulers had been converts to Christianity for 200-300 years (see article here). In these lists Cooper aligns “Seskef” from the Icelandic lists with “Sceaf” (see discussion of “Sceaf” in earlier show note). Cooper leaves out, however, the list of names between Seskef and Noah given in the Langfethgatal (see pgs. 56-58 here) and in Snorri’s Prose Edda (see pgs. 6-7 here) where the list doesn’t go back to Noah, but instead goes from Seskef back to the king of Troy. Cooper suggests that these differences support the case that the lists are independent, rather than simple copies of one another (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (pp. 87-88). Chapter 7. Kindle Edition). Cooper also includes the comment that a lack of “Noah” in some of the lists undermines the argument that these were forgeries intending to link a king back to Biblical history (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 87). Chapter 7. Kindle Edition) (if the goal was to link to Noah, why would you leave out Noah?) a point on which I think Cooper’s argument has merit.

The Irish family tree that links them to Magog and Japheth is given in a number of different places in the book here (see pgs. 63, 75, 82, 95, 121, 125, with pg. 95 having the list referenced in the index). Though Cooper references Keating as a source, the version of the family tree he gives in After the Flood (p. 96). Chapter 8. Kindle Edition has a slightly different structure. While I couldn’t tell which version of the family tree I should use, the legends do appear to consistently trace the family back to Magog.

In an earlier table in his book, Cooper gives names from Nennius, but they come as descendants of Japheth through Javan instead (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 40). Chapter 3. Kindle Edition). Nennius was an author from around 800 AD who collected various history. The above source considers his material largely fictional but perhaps with some small historical pieces. Cooper defends Nennius, noting that Nennius collected and transmitted the stories without editing them to even fix discrepancies, which can be seen as evidence of truthful transmission of error rather than covering up the error by trying to correct the differences in the legends (see Cooper, Bill. After the Flood (p. 36). Chapter 3. Kindle Edition as well as Appendix 5 in the same book). Another author, independent of Cooper, argues similarly on pg. 6-7 here suggesting that Nennius was a collector of old material and offers some support for his honesty in that he didn’t correct errors in material he passed along. The opposite view is mentioned here which shows that Nennius’ story of a Saxon massacre of Britons bears suspicious similarity in various details to legends from Byzantine history and the founding of Carthage, while another article that more-or-less completely dismisses Nennius can be found here with the conclusion on pgs. 671-672. Those contrasting opinions stated, Nennius does describe collecting a “heap” of material, so where one part of his annals might be legend and fiction, it doesn’t preclude other parts from being a more accurate transmission of history. Cooper suggests the discrepancy between whether the Irish were descended from Magog vs Javan is due to mixing of families prior to the dispersion from Babel (see chapter 8), though to explain all the discrepancies, some muddling of the records is also likely.

For the reciting of genealogies at social and religious functions in Ireland, see pgs. 328-329 here which points out that keeping genealogies accurate was a way of maintaining reputation and status… but then goes on to argue that later on ancestors were “supplied” to give people a link to the Bible without noting that it would be difficult to make a change as everyone in society would have to change their family trees or it would upset the social structure. In another source, on pgs. 46-47 here, the author records how the Irish kept strict records of their genealogies for both “social and political” reasons and that these records were checked against one another every three years at Tara, the home of the Irish kings (see pg. 125).

For details on the Ural mountains which form the border between Europe and Asia, see here. For a map of the Ural mountains and a list of some mountain peak heights, see here.

Update: On 3/19/2025 I modified the introduction paragraph and updated links to Bible copyright information.